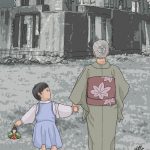

‘Loss in Hiroshima’

11,00€ – 33,00€

Art print on handmade Japanese paper.

Natural fibers and elements are used in the creation process, without the presence of acids or bleaches.

The pigments used, through the giclée process, are long-lasting and of archival quality.

Although the print can be framed, perhaps the best way to enjoy the appearance and texture of Japanese paper is to hang it as a scroll. In this way, you can appreciate its virtues not only through sight, but also through touch and hearing.. and even smell!

In this link you will find custom made ‘Scroll Rods’, handcrafted using Paulownia wood and authentic Japanese Kakeo —string for hanging scrolls—:

setsuko-monogatari.com/en/hiroshima-ken/scroll-rods

Since it is a translucent handmade paper, it is recommended to hang the print with a white wall background, in order to emphasize the light of the Station and that of the paper itself. If the wall is dark, it is advisable to place a white sheet just behind the Station.

At this Station..

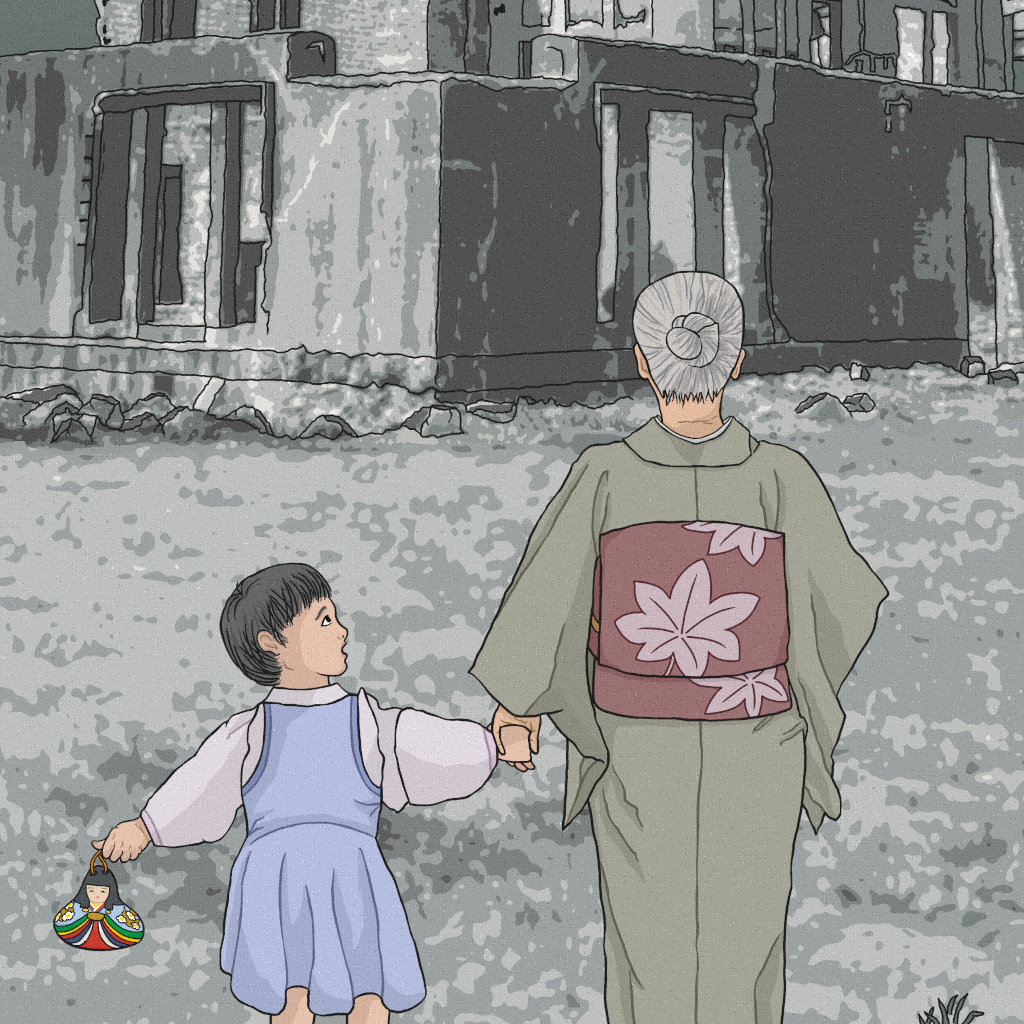

KŌGEI: ‘Miyoshi Ningyō’ —clay doll that is usually given to children to wish them to grow up healthy and happy—

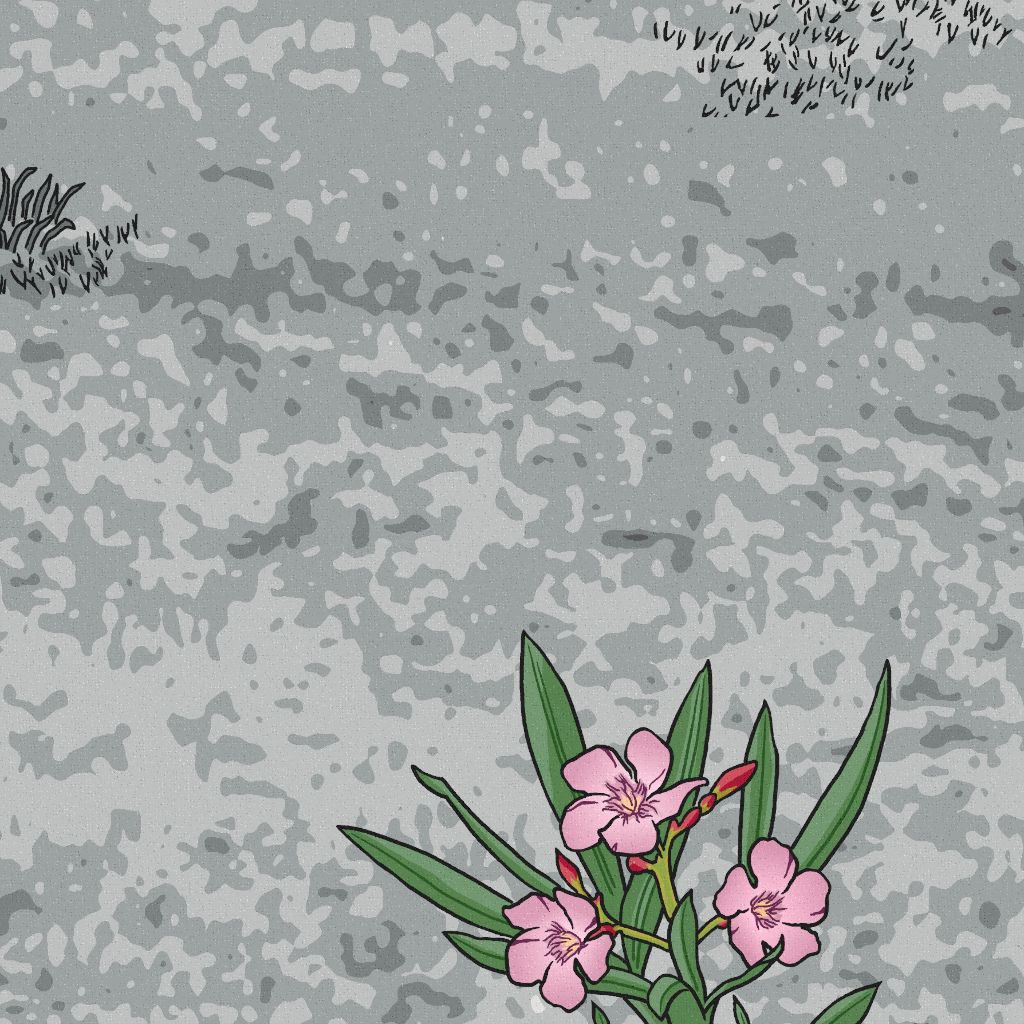

SYMBOLS: ‘Hiroshima Heiwa Kinenhi’ —Hiroshima Peace Memorial—, Maple (prefectural tree and flower) and Nerium oleander (first flower to bloom in Hiroshima after the bombing)

Station founded in..

One summer morning in 1945, the history of Hiroshima, of Japan and of the entire world changed.

The atomic bombing that took place that day claimed tens of thousands of lives in an instant. Three days later, in the city of Nagasaki, it would happen again.

Over the following months, the effects of this atrocious act continued to take the lives of a great number of people, due to the radiation to which they were exposed, and to the wounds and burns that this attack caused. And, in turn, they also extinguished lives that were inside others, and that had not yet begun to live.

Time went by, and the war ended. But the wounds remained.

For those who managed to survive, from that fateful day, their lives would change forever. Against their will.

It would be a life full of complications, full of painful situations, as every life has them. But such should never have happened. Those were not the lives they should have lived.

For the hibakusha —the Japanese term that designates the people affected by the bombing—, every day was August 6th.

The reconstruction of the city was progressing little by little, and public services were being restored. But for them, their heart and their spirit had been casted down, and it would take time to recover them, if ever.

Horror and death were always present in their minds. And they were torn in a constant dilemma between hiding their pain until it disappeared, or seeking understanding.

Many of them decided to start new lives elsewhere, which gave them hope and allowed them to regain their enthusiasm. But upon arriving at their destinations, what awaited them was rejection and discrimination.

They were going to suffer the prejudices of an uninformed society, which put their dread before their reasoning. They were discriminated against when it came to finding employment, at the time of formalizing marriages, and during maternity. As well as in any other facet that we can imagine, which involves the fact of being accepted as a member of a society.

People believed that they would die in a few years, that their days were numbered. They believed it was something contagious and, moreover, hereditary. And that, therefore, it was a recklessness to start a relationship that would be considered long-lasting.

For that reason, there were those who concealed their origin, denying that they were natives of Hiroshima. And there were even those who changed their own name.

Even so, they continued forward, writing their story. Somehow, they had been given the opportunity to keep living. And they weren’t going to waste it.

They raised families, worked with effort, and brought new life into the world. To someday be able to explain to them that they had been there, and that they had struggled to survive one of the great mistakes of humanity.

The years went by, and the feelings of pain and resentment were slowly dissipating. But in spite of that, many hibakusha decided to bury their memories, and never speak again about what happened. The stigma with which society had paid them, continued to weigh on their shoulders.

Still, even though their inner conflict would linger, there was something else in their being that would also remain unchanged.

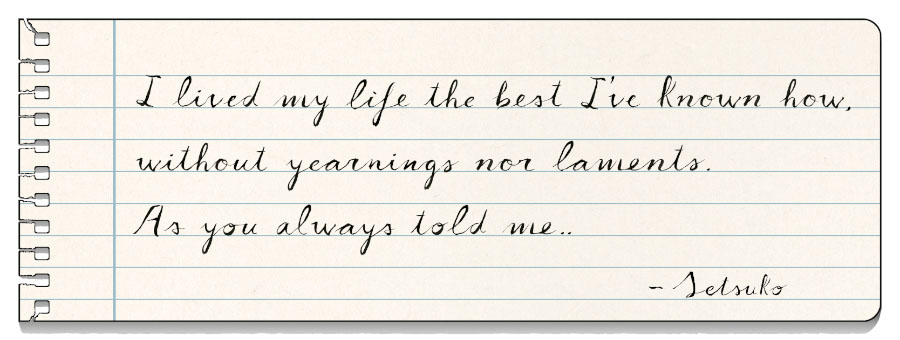

The voices of their loved ones would not cease to echo in their minds. And they would do so, at all times, with a single message: ‘Don’t hide yourselves, you have done nothing wrong. Tell your story.’