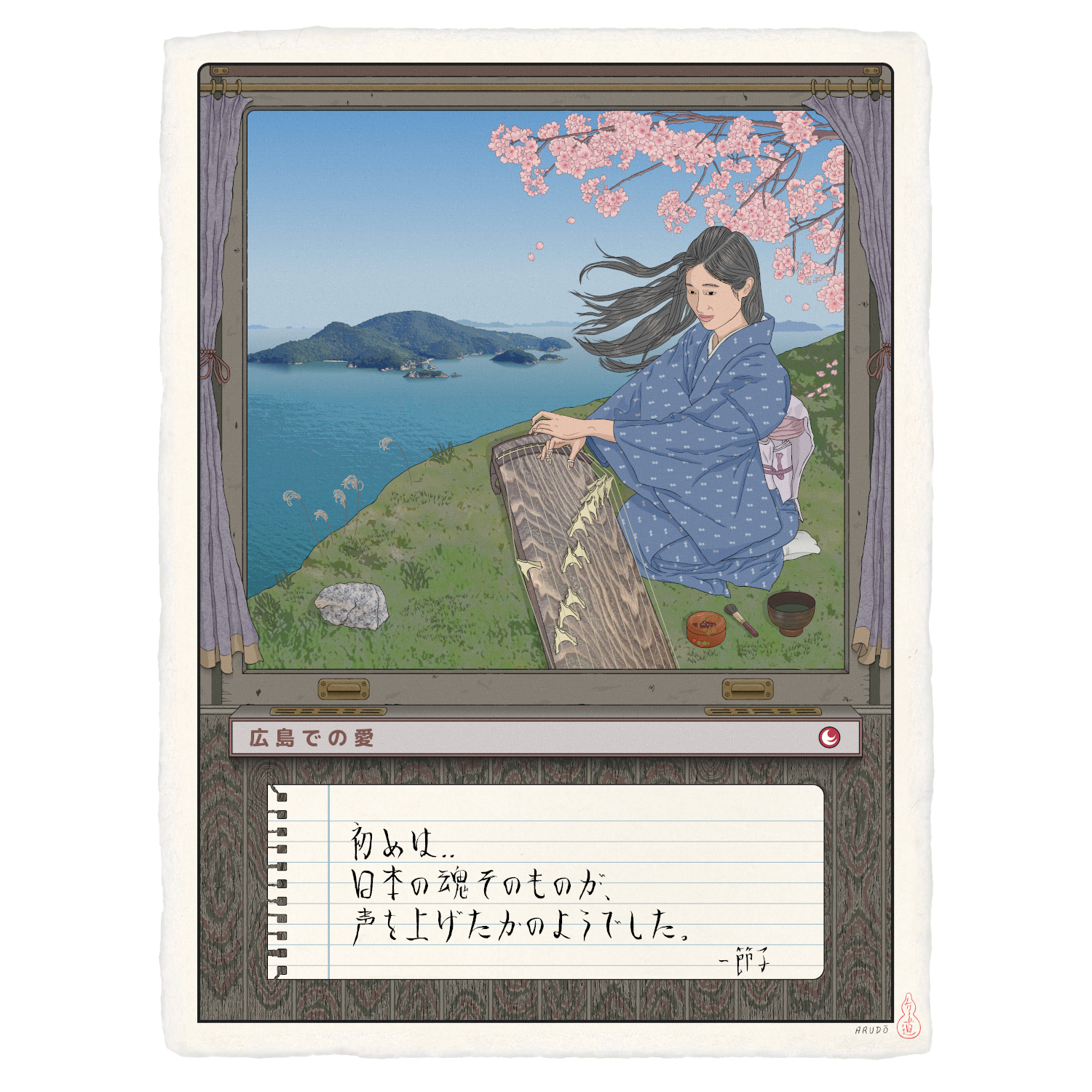

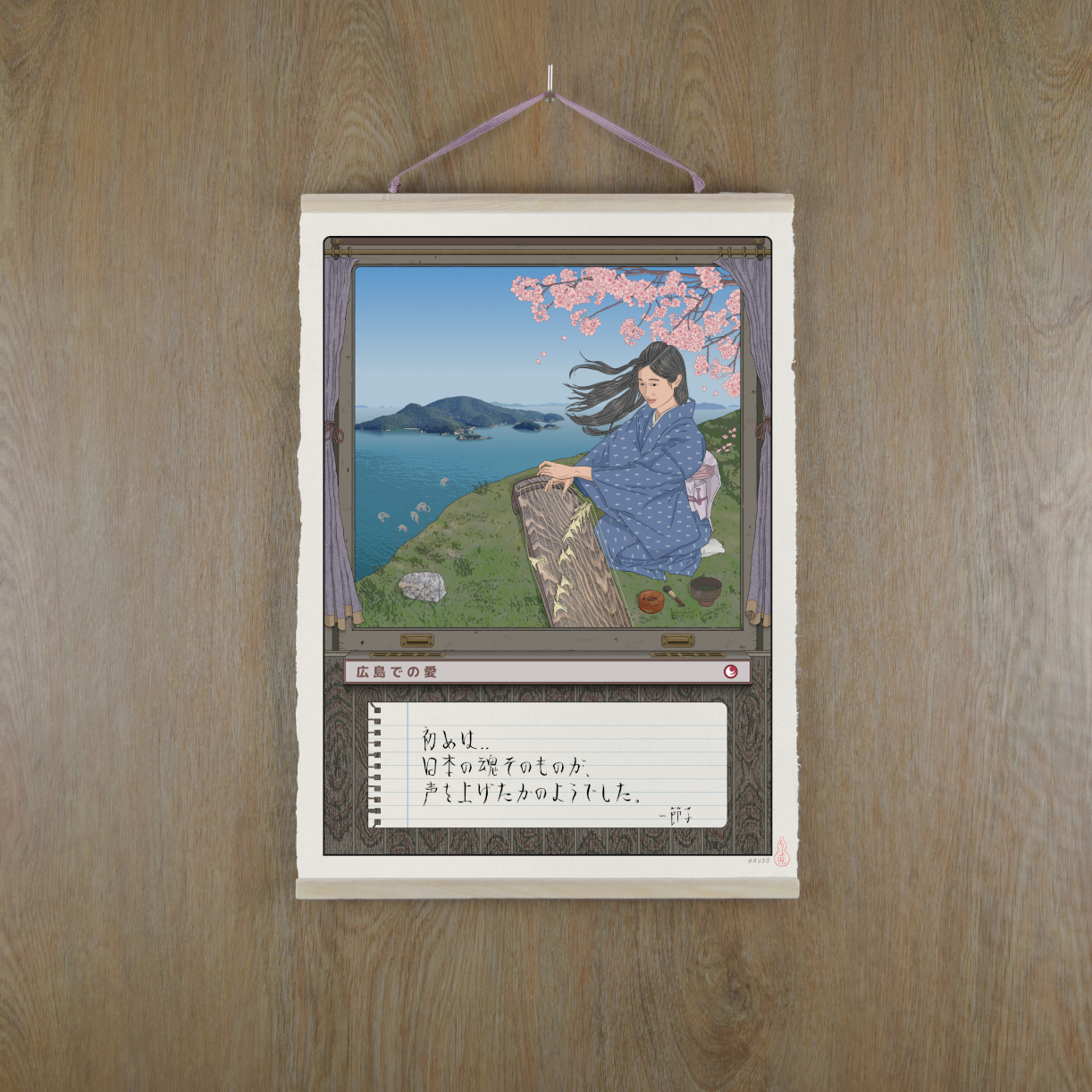

‘Love in Hiroshima’

11,00€ – 33,00€

Art print on handmade Japanese paper.

Natural fibers and elements are used in the creation process, without the presence of acids or bleaches.

The pigments used, through the giclée process, are long-lasting and of archival quality.

Although the print can be framed, perhaps the best way to enjoy the appearance and texture of Japanese paper is to hang it as a scroll. In this way, you can appreciate its virtues not only through sight, but also through touch and hearing.. and even smell!

In this link you will find custom made ‘Scroll Rods’, handcrafted using Paulownia wood and authentic Japanese Kakeo —string for hanging scrolls—:

setsuko-monogatari.com/en/hiroshima-ken/scroll-rods

Since it is a translucent handmade paper, it is recommended to hang the print with a white wall background, in order to emphasize the light of the Station and that of the paper itself. If the wall is dark, it is advisable to place a white sheet just behind the Station.

At this Station..

KŌGEI: ‘Ikkokusai Takamorie’ —lacquered wood craft—, ‘Bingo Kasuri’ —weaving of simple and timeless patterns—, ‘Kumano Fude’ —brushes for painting, writing and makeup—, ‘Togouchi Hikimono’ —wooden items created by lathe— and ‘Koto’ —national instrument of Japan—

SYMBOLS: ‘Tomonoura’ —port of Fukuyama City— and Granite from Hiroshima (prefectural rock)

Station founded in..

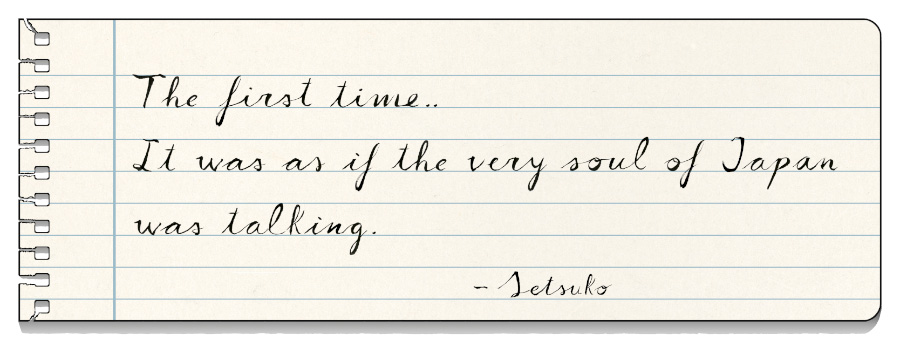

On some occasions, it is not necessary to have traveled to Japan to feel you have been there. That feeling can be found by reading its literature, contemplating its art or learning its language.

In the case of its music, there is an instrument that has the power to transport you to the land of the rising Sun in an instant, not only through space, but also through time.

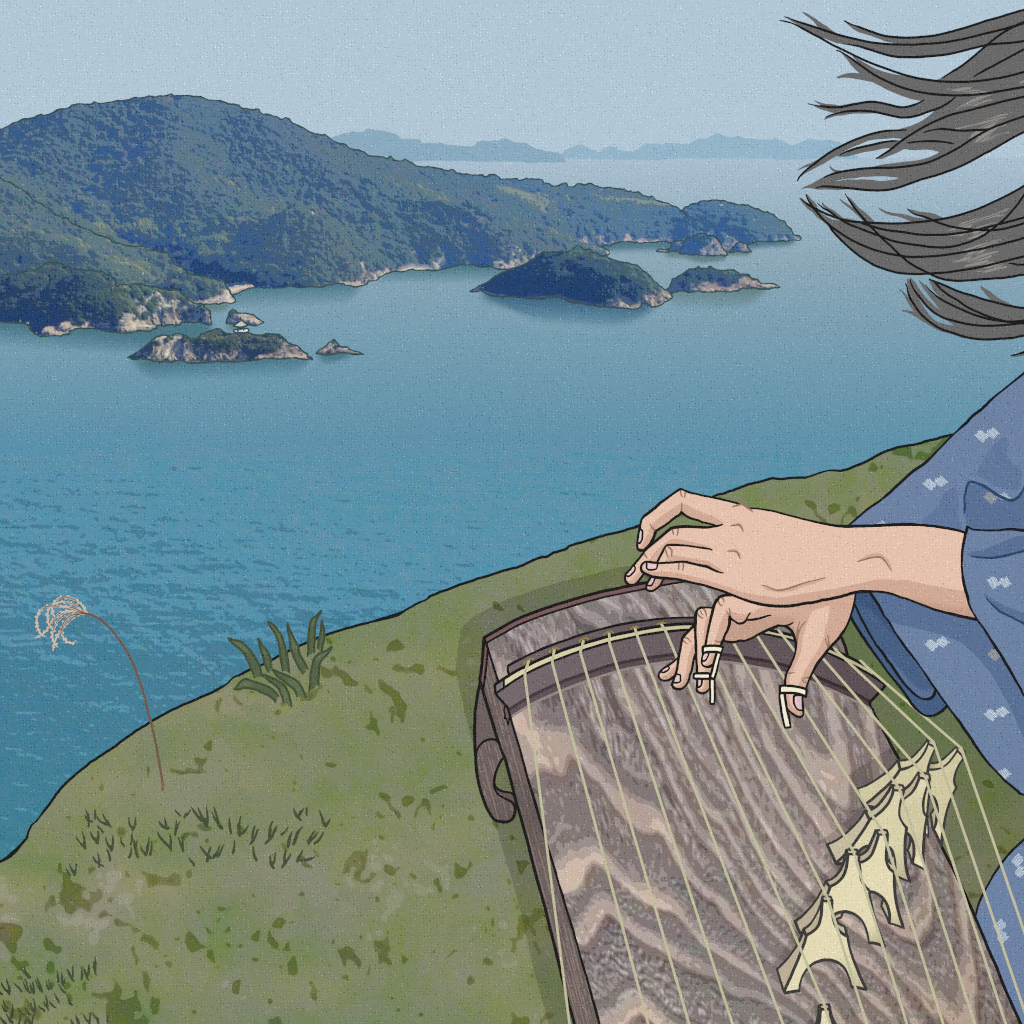

The Koto, between its backboard and its soundboard of paulownia, and throughout its silk strings, harbors an intricate history of more than 1,300 years old.

Just by observing its materials, we can already discover in it profound layers of historical significance.

Paulownia wood has had auspicious connotations in Japan since remote times. On the birth of a daughter, it was customary to plant a Paulownia tree in the home, which would mature at the same time as she would. And when the daughter would reach maturity, her parents would present her, on her wedding day, with an ark made from the wood of that same tree.

For its part, the importance of the Silk Road as the main conduit for cultural exchange between East and West, would show us the immeasurable value that this material possessed in the ancient world.

But the symbolism of this instrument still would acquire a more singular, even supernatural, meaning with its own body. For centuries, the Koto was associated in people’s imaginary with the figure of the dragon. Its soundboard represented the body of one, covered with wooden scales, while its raised end was its head. And so, each part of the instrument would find its equivalence in the body of this mythological being: from its stomach and navel, through hands, legs and tail, up to its lips, eyes and horns.

The dragon has an immense relevance in Japanese culture and, since ancient times, it has been linked to strength, good luck and natural phenomena such as rain. Thus, it is not surprising that it would also reached other spheres of such culture, as is the case of art and poetry.

Unlike other cultures, in Japanese folklore, the dragon is not associated with fire, but with water. Therefore, the movable bridges that made up the Koto would not only be equivalent to its backbone, but would also give rise to new artistic interpretations.

The iconic scene of a flock of wild geese soaring a lake on their way home, would inspire the mind of artists and poets, who would make them fly over the sea back of this 13-stringed dragon. Just as music flies to our ears.

The practice of Koto, from its origins in the court period to the present day, has not only formed the basis of a millenary musical tradition.

The importance of social convention and etiquette, the sense of belonging to a group, the respect for the past. Values, all of them, that have been passed down for centuries, acting as cohesive elements of Japanese society.

That is why, nowadays, we can observe a cultural dichotomy between their world as performers, and their lives outside such traditional society. A sensory perception akin to walking between two worlds: the world we can see with our eyes, and the one we cannot.

Likewise, an isolated event in history would lead to the introduction into that world of a social group in particular, which would predominate in its practice for centuries: blind male musicians. The story goes that the sudden blindness of an emperor’s son, during the Heian period, would have as a consequence that all musicians of a particular tradition, from that moment on, would also have to be as well.

And so, centuries later, during the Edo period, blind performers would be responsible for the popularization of the Koto, whose practice had been reserved for the aristocracy since distant times. But their presence, in turn, would centralize the everyday life of this instrument, excluding women and sighted men from its practice.

Even so, the spread of such a captivating sphere surrounding the Koto, attracted the Samurai warrior class. Who considered it appropriate for their daughters to learn to perform it, as a sign of social refinement.

And, ironically, those same women who had been excluded from its practice for centuries, would achieve, as in so many other fields, the survival of this instrument during the tumultuous social changes that the country would experience. And her figure, by the hands of poets and artists, would remain eternally associated with the Koto in the collective imaginary. As a symbol of a traditional Japan, of a nostalgic past, perhaps even idealized, of an earlier era.

Fukuyama is the city known for being the main producer of Koto nationwide. And it was in the spring of one of its districts, where the view of the sea from the port of Tomonoura, would inspire one of the most beautiful songs that have ever been composed.

A flood of emotions can be expressed through the Koto, so diverse and, at the same time, so consubstantial of the human being. And it is that the creation of such lovely compositions by blind persons would show us that, on some occasions, eyes are not necessary to be able to see the heart of things.