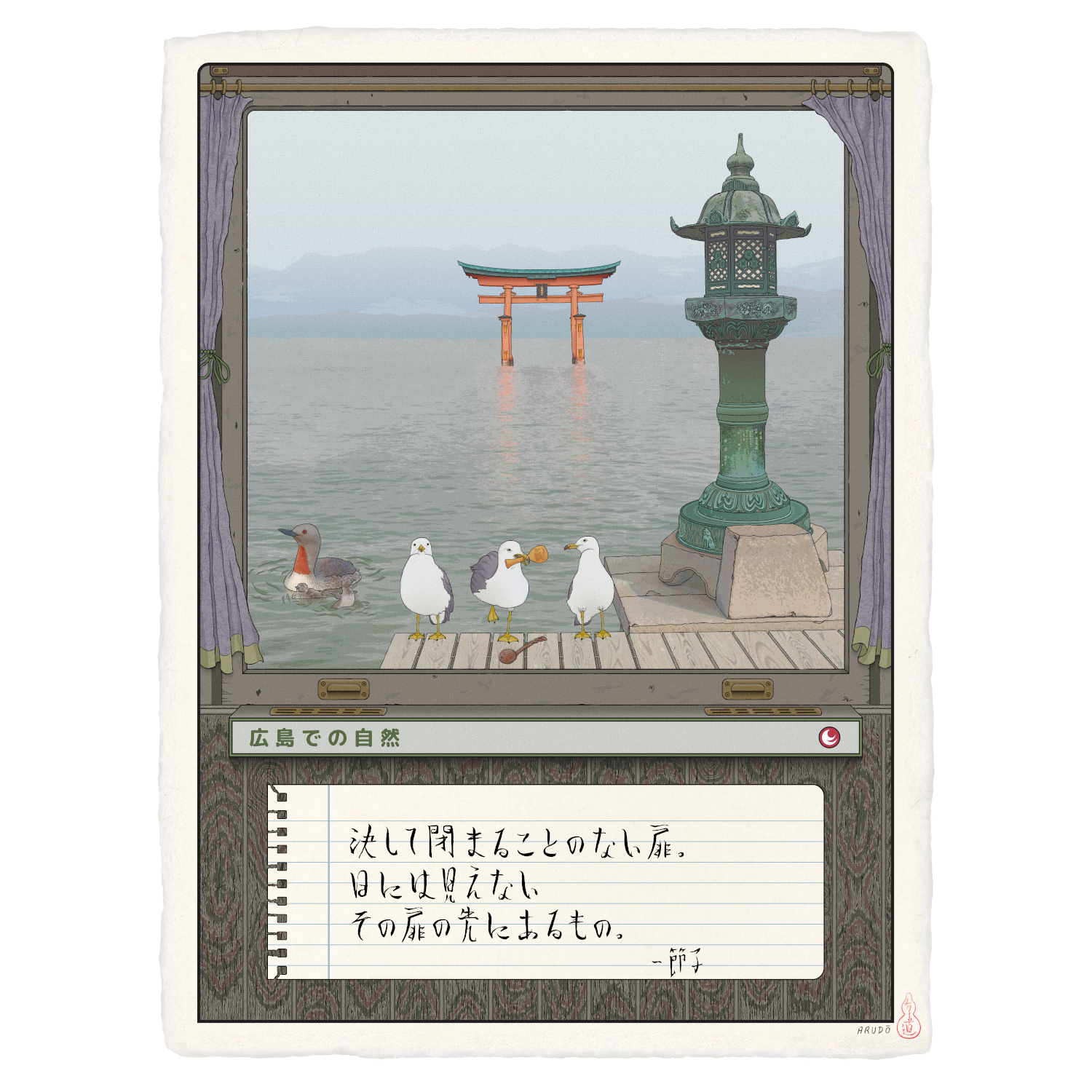

‘Nature in Hiroshima’

11,00€ – 33,00€

Art print on handmade Japanese paper.

Natural fibers and elements are used in the creation process, without the presence of acids or bleaches.

The pigments used, through the giclée process, are long-lasting and of archival quality.

Although the print can be framed, perhaps the best way to enjoy the appearance and texture of Japanese paper is to hang it as a scroll. In this way, you can appreciate its virtues not only through sight, but also through touch and hearing.. and even smell!

In this link you will find custom made ‘Scroll Rods’, handcrafted using Paulownia wood and authentic Japanese Kakeo —string for hanging scrolls—:

setsuko-monogatari.com/en/hiroshima-ken/scroll-rods

Since it is a translucent handmade paper, it is recommended to hang the print with a white wall background, in order to emphasize the light of the Station and that of the paper itself. If the wall is dark, it is advisable to place a white sheet just behind the Station.

At this Station..

KŌGEI: ‘Miyajima Zaiku’ —natural wood items in warm tones— and ‘Togouchi Kurimono’ —utensils manufactured by woodcarving—

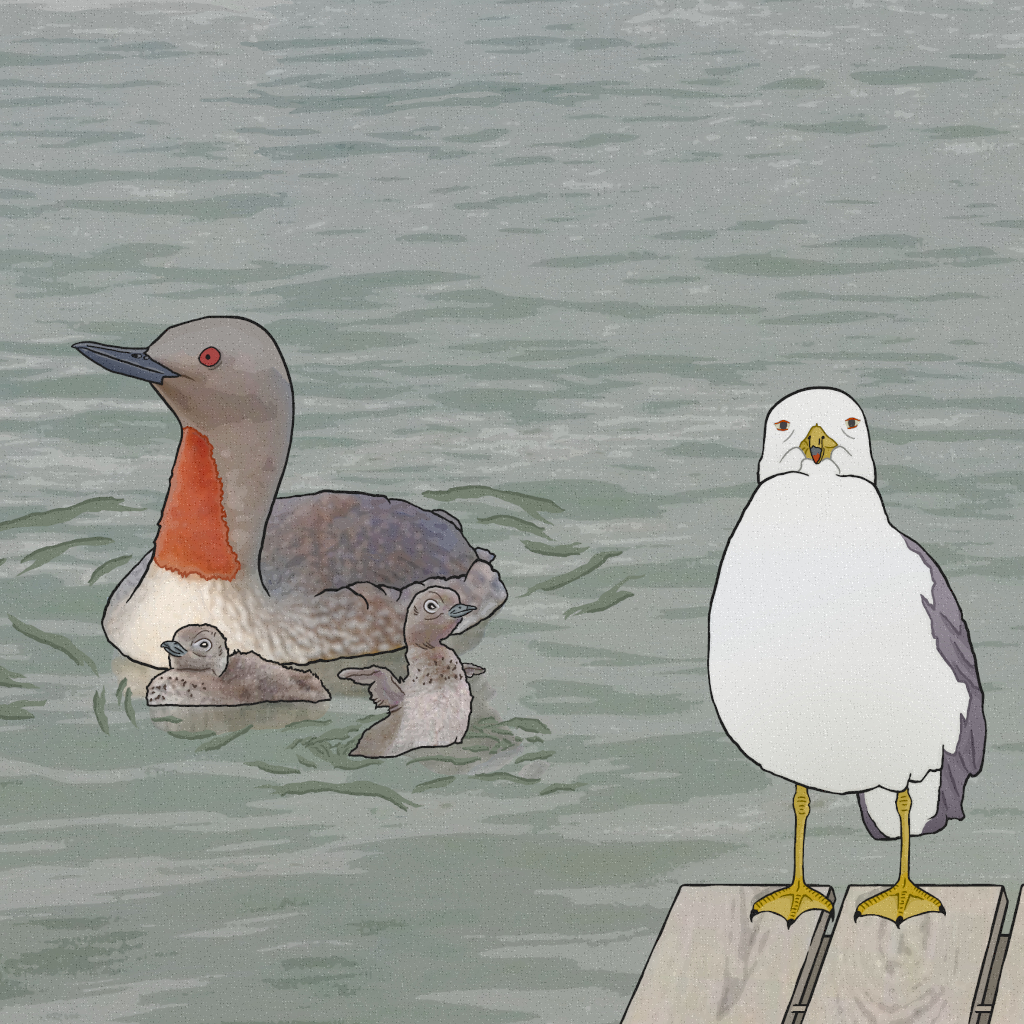

SYMBOLS: ‘Itsukushima’ —historical island known as ‘shrine island’— and Gavia Stellata (prefectural bird)

Station founded in..

Since before being aware of its own existence and mortality, the human being wanted to understand. It was long before the first sign of formal communication appeared. They may not have had a specific way of expressing it, but the feeling of awe and excitement that such majesty aroused in them, was very real. Something that, centuries later, would be called Nature.

The forces of the natural world were present at all times. With the rising of the Sun, with the coming of darkness. With the irruption of the water, and with its flight.

The mysterious powers that gathered storm clouds, and that made the wind roar, the thunder rumble and the lightning flash. All of this was beyond their comprehension.

They could observe how certain animals and plants, which constituted their sustenance, on some occasions, disappeared.

And so, in that world of common experiences, far from any remote equilibrium, and that evoked feelings of caution before the manifestation of the unknown, the inevitable occurred: a distinction arose, between the earthly world of humans and an esoteric world where ancestral spirits dwelled.

A place where supernatural entities represented all that was strange, fearsome, uncontrolled and prodigious about the land they inhabited. In ancient Japan, such spirits were known as Kami.

The oldest chronicles has it that the two original Kami were sent to earth from that distant world located in the firmament, called Takama-ga-Hara —the Plain of High Heaven—. And how they begetted the eight islands of the Japanese archipelago.

In that land between seas, Izanami-no-Mikoto and her brother and consort Izanagi gave life to other spirits, as well as to all living things in nature. Creating, in turn, mountains and rivers, trees and rocks, fields and seas.

Izanami was presented as the ancient mother earth, generator of life and fruit. Izanagi, as the old father sky, from whose eyes arose the Moon and the Sun. In the conjunction of both, the cycle of life was observed, and the severe crises that seasonal change generated.

With the death of her and her retreat to Yomi-no-Kuni —the Land of Darkness—, she was taking her garments and ornaments with her, leaving the land dry and desolate.

Throughout history, the mythology of ancient peoples emerged from momentous events that affected their life in society. And behind every myth, lied intrinsic a human need. The pressing need to subsist, and to adapt to a hostile and constantly changing environment. If human as an individual was to live, must had food. And if human as a race was to persist, must had offspring. To live and to cause life.

Over the course of the ages, Shintō —the way of the Kami— would be enshrined as a ceremony of gratitude to the ancestors and to nature. As a ritual that, generation after generation, would transmit an underlying way of seeing existence, and acting accordingly. A millenary wisdom that would define the thinking of a people, through a concept that resembled both the surface water of a well, and its immense depth: acceptance.

It was a people who felt the weight of nature, and feared its destructive power. But at the same time, they were enfolded by a feeling of gratitude towards the abundance of it. Two sides of a single reality, which reflected their belief in honoring all that surrounded them.

In appreciating that if the land delivered rice, if the sea provided catches and if the sky granted water, it should be so. But if the earth trembled, the sea shook and the sky flooded, it also should be so.

That way, each of the events that transcended the capacity of the human intellect was considered Kami. Such spirits symbolized the mythological projection of that fear and of that gratitude.

They felt its presence everywhere. Everything had a spirit, regardless of its size or shape, regardless of its condition as a living or inert being. They inhabited in all things. Trees, plants, rocks and waterfalls. Birds, foxes, wolves and badgers. Also in the echo dwelt a spirit.

The ancestors, likewise, were considered Kami: family members, sages, heroes or emperors of an earlier era, whom they honored. Paper, as well, was so, because of its unusual importance in social progress. And even in the hair itself resided a spirit, because of its primitive association with a mysterious superhuman power.

The earliest veneration of the Kami did not take place in man-made shrines. Mountains, forests or springs served as primitive shrines.

And to keep impure elements and evil away from their entrance, they began to build a gateway. A portal called Torii, which not only protected them, but also marked the transition between both worlds. Raised by two pillars, like living trees, anyone who traversed it must always do so on one side. Although it might seem that no one else was crossing it.

And so, this millenary wisdom would be transmitted, for centuries, from masters to disciples, from parents to children, from old to young. A timeless relationship between nature and human. Eternally renewed with the rising of the Sun every day, and with the passing of the seasons every year. An eternity that is neither physical nor material, but spiritual. Where the meaning of life is not found in the future, as this doesn’t exist. There is no time but the now, an eternal now.

A present in which to live with joy and gratitude, in harmony with all beings around us.

For a brief time, we will be able to enjoy it. But inherent in it, is also the duty to preserve it. Until the next generation does it.

To respect the environment, and to learn from it. And to learn from how other beings learn from it. The natural world is not an object we can use at will. Nor is it something that is there to make more pleasant our existence. It is an equal.

We are only one more, one of the millions of beings that inhabited and that will inhabit this earth. We are important if we are useful. But, at the same time, we are insignificant, a whisper in time. To coexist with this balance between the importance we give to our being, to our own existence. And, at the same time, to be able to abstract ourselves from it, and to contemplate immensity and eternity. It is humbling.

It may surprise that in every being, in every entity of the natural world, resides a spirit. But in fact, when everything around you has a soul, you stop thinking only of people.

And then, you perceive that you are not only connected with nature, but that you are interwoven in it. It is at that moment, when you feel that you are just another part.

After all, the Plain of High Heaven may not have been a place, but a state of mind.